The Louvre: The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities

The Louvre: The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities

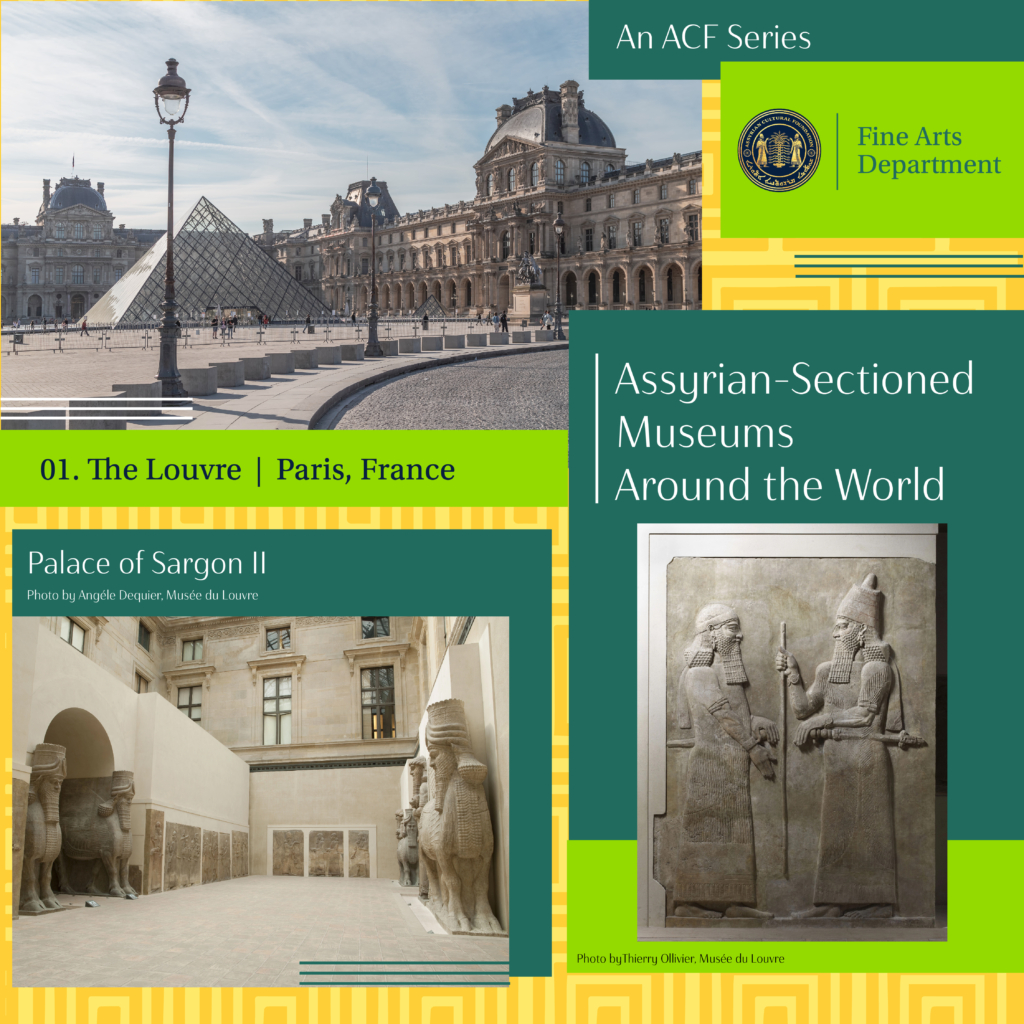

Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

The first ever museum collection of Assyrian artifacts began in 1847 with the Musée de Louvre in Paris. The first, and some of the most noteworthy, pieces from this collection were uncovered at Sargon II’s Palace at Dur-Sharrukin. The remains of this ancient palace reside in what is now modern-day Khorsabad, Iraq. The palace at Dur-Sharrukin began construction under the reign of Sargon II. The King had intended to establish a new Assyrian capital at Dur-Sharrukin as a way of asserting his authority. Dur-Sharrukin was on its way to becoming the largest city in the ancient world. However, upon his untimely death, Sargon’s son and heir, Sennacherib, moved the capital to Nineveh, leaving the palace at Dur-Sharrukin behind unfinished. After the fall of the Assyrian empire in the 7th century, the artifacts of this great nation were buried by both literal and metaphorical sands of time. The Bible, as well as select ancient Greek texts, remained the only literary recourses Western archeologists and explorers had to learn about ancient Mesopotamia up until the mid-19th century. Though, sources such as the tale of Ahiqar the Wise, Ahiqar Hakima, as well as other writings in Syriac or Aramaic kept the memory of the great nation alive in the Assyrian community. The rise of European interest in ancient objects, coupled with the political interests of Britian and France, initiated a series of excavations in the middle east conducted by these foreign governments.

Paul-Émile Botta was a French Consular Agent in Mosul, who had been selected to lead the excavation due to his background as a naturalist, historian, and diplomat, as well as his ability to speak multiple languages. He initially began digging at Quyunjik, but was unsuccessful in unearthing any major discoveries. Based on advice from local citizens, Botta turned his attention to Khorsabad in hopes of discovering undisturbed artifacts. Compared to other Assyrian monuments, Dur-Sharrukin was buried fairly close to the surface, and within a week’s worth of digging, Botta’s team was successful in uncovering large sections of the palace.

The Palace of Sargon II contained a number of groundbreaking discoveries. Botta and his team unearthed large gypsum alabaster slabs which featured bas-relief sculpture telling the story of King Sargon’s royal life and legacy. This included scenes of hunting and military campaigns, as well as depictions of Assyrian gods. These alabaster slabs lined the mud brick walls of the sprawling palace, which contained around two hundred rooms and courtyards. The doorways were flanked by Lamassu statues; the first of their kind to be discovered by archeologists.

Given the significance of Botta’s discoveries, the French government supplied the team with further resources for excavation and documentation. This included sending artist Eugène Flandin, who illustrated the site and finds. Time was of the essence when it came to illustrating the artifacts, as being suddenly exposed to the desert elements and heat started to damage them. Soon after unearthing the objects, Botta began shipping them back to France by way of boats up the Tigris River. This process was fraught with difficulty. The sheer amount and size of the objects being transported overwhelmed the ships. Throughout the journey, the crews were attacked and seized by pirates, who managed to sink one of the ships. In an effort to make the transportation process easier, some controversial choices were made. This includes breaking artifacts into smaller pieces and then reassembling them onsite at the Louvre. By today’s standards, Botta’s transfer of antiquities can be seen as a lesson in “what not to do.” However, the challenges faced and mistakes made did help to inform later academics in developing standardized and regulated means by which valuable historical objects are acquired, handled, transported, and maintained. Given that this was the first ever major excavation in the Near East, they still had a lot to learn.

After their treacherous journey, the objects arrived at the Musée de Louvre in February of 1847. On May 1st 1847, King Louis-Phillip inaugurated The Ninevite Museum. This was the first exhibition of Assyrian antiquities in the world, and there was a great deal of public interest in the collection. In the years to come, the collection continued to expand. Contributions were made by Ernest Renan in the 1860’s, and Ernest de Sarzec in the 1870’s. Sarzec discovery of Ancient Sumerian objects prompted the Ninevites Museum’s transition into The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities in 1881. At this time, Léon Heuzey was appointed head curator of the department. He was incredibly devoted to garnering recognition of and knowledge about the antiquities, and also worked as a professor in Near Eastern Antiquities. Today, The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities at the Musée de Louvre remains one of the most remarkable collections of ancient Assyrian artwork in the world. Assyrians have had their own history systematically obfuscated from them from centuries. This has been done both through the separation of the community from their native homeland, and through the destruction of historical artifacts. Though the process of the excavations of these artifacts was imperfect, the exhibitions provide modern Assyrians the ability to stand face to face with their own history during a time when that is becoming increasingly more difficult. Assyrians can also take pride in knowing how significant and awe inspiring their history is to the global community, who continue to flock to the Louvre to experience the wonders of The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities. After all, they are the decedents or the artisans and laborers who’s work now contributes to the prestige of this world rebound museum.

Written by: Melanie Perkins

Published by: Brian Banyamin

Bibliography:

“Early Excavations in Assyria.” Metmuseum.org, Aug. 2021, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rdas/hd_rdas.htm.

“The Opening of the Assyrian Museum at the Louvre.” Gouv.Fr, https://archeologie.culture.gouv.fr/khorsabad/en/opening-assyrian-museum-louvre. Accessed 16 Jan. 2023.

“The Palace of Sargon II.” Le Louvre, https://www.louvre.fr/en/explore/the-palace/the-palace-of-sargon-ii. Accessed 16 Jan. 2023.

Albrecht, Lea. “Louvre Shows Mideast Relics with Dubious Past.” Deutsche Welle, 23 Nov. 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/louvres-mesopotamia-exhibition-highlights-europes-spotted-past-with-ancient-art/a-36490045.

Wikipedia contributors. “Dur-Sharrukin.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 28 Dec. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Dur-Sharrukin&oldid=1129976094.