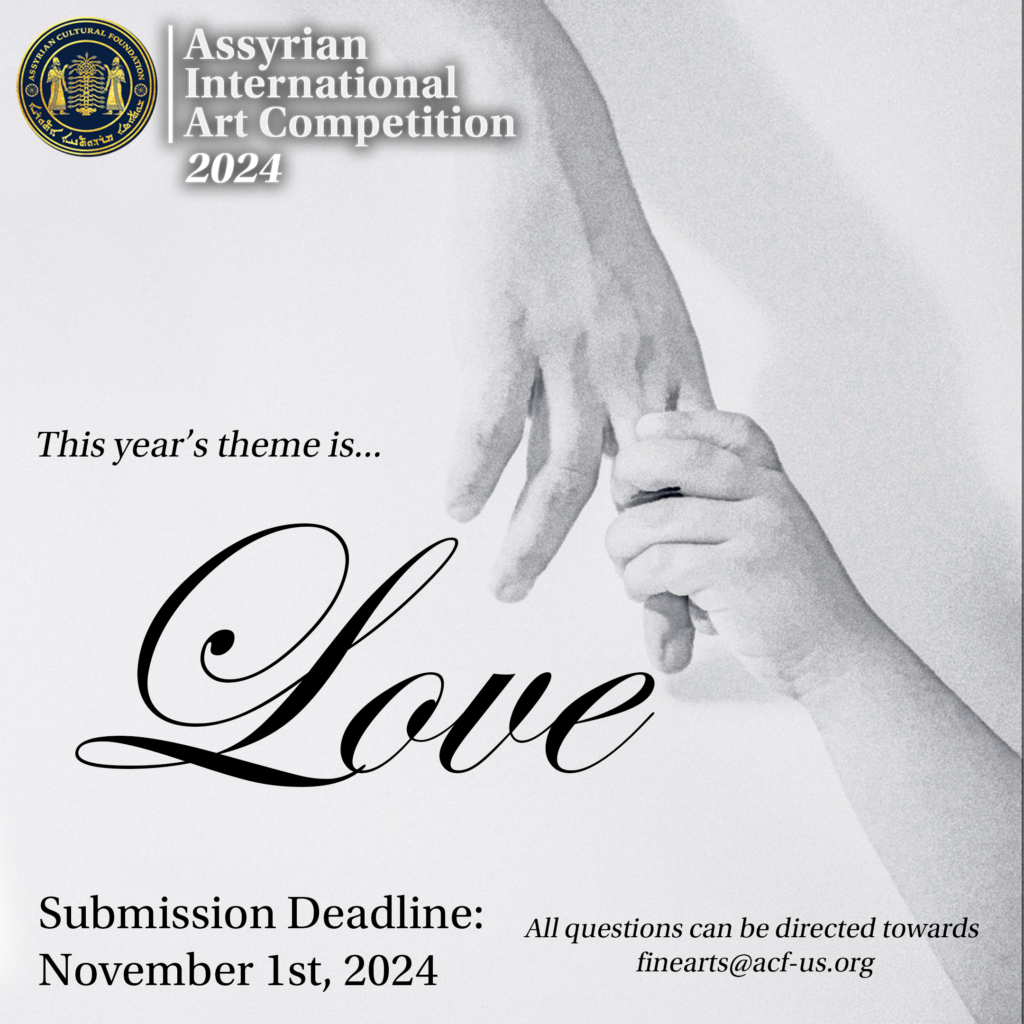

2024 Assyrian International Art Competition Rules

Date: January 19, 2024

At the Assyrian Cultural Foundation, we value the deep impact art can have on individuals across the world. A single painting can illustrate the richness of a culture, the resilience of a group of people, and the power of love. It is our mission as a Foundation to highlight the importance of art within our culture, as well as some of the brilliant Assyrian artists still practicing today.

From this, the Assyrian International Art Competition was born. Over the past few years, we have seen a range of gorgeous work produced by wildly talented Assyrian artists across the world, and we are excited to shine a light on even more of these individuals this year.

Love is the theme for the 2024 Assyrian International Art Competition. The final deadline for submission is Friday, November 1, 2024. You may submit to the competition at any point leading up to that date but are not permitted to submit after the deadline. Below are the submission requirements.

- Submitted works must reflect the year’s theme. You cannot submit a previous work from your collection. It must be an original design that does not violate any U.S. copyright laws.

- The submitted piece must be in a 2D medium. Acceptable mediums include painting, drawing, collage, or mixed media (a combination of the aforementioned mediums). Digital art will not be accepted. The use of AI will result in immediate disqualification.

- The piece must be a minimum of 5ft² (or 4645.15cm² in metric).

- You may not submit any work that has been published in any capacity, including submissions to previous art competitions, submissions to physical or virtual galleries, works sold as prints, or works that were posted on any social media platform (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, your personal website, etc). Doing so will result in disqualification.

Once you are satisfied with your piece, you may submit your artwork to us. Doing so is simple:

- Fill out the application form provided on our Fine Arts Program page. This includes a space for a brief artist statement to elaborate on the work and its relation to the theme in no more than 200 words.

- Once you have completed the application, you may submit the form along with three high-resolution pictures of your work to finearts@acf-us.org. The images must be at least 1080×1080 pixels in size in a JPG or PNG format. Do not include any filters or watermarks on the image.

You will be notified if your piece was selected as one of the Top 10 Finalists. These pieces will be shared across our social media in early November, followed by the top five later in the month. The top three will be unveiled in early December. The top three finalists will be asked to mail their works to the Foundation for final judging. Shipping costs of up to $500 will be reimbursed.

Please keep in mind that winning submissions become the exclusive property of the Assyrian Cultural Foundation in exchange for the prize money. ACF reserves the right to display, publish, and promote the item in any capacity upon the work’s acquisition. Finalists are subject to U.S. federal, state, and local taxes on their winnings, with international winners subject to a 30% tax deduction on winnings as per the U.S. federal tax code.

Good luck! We eagerly await the arrival of your inspirational pieces of artwork.