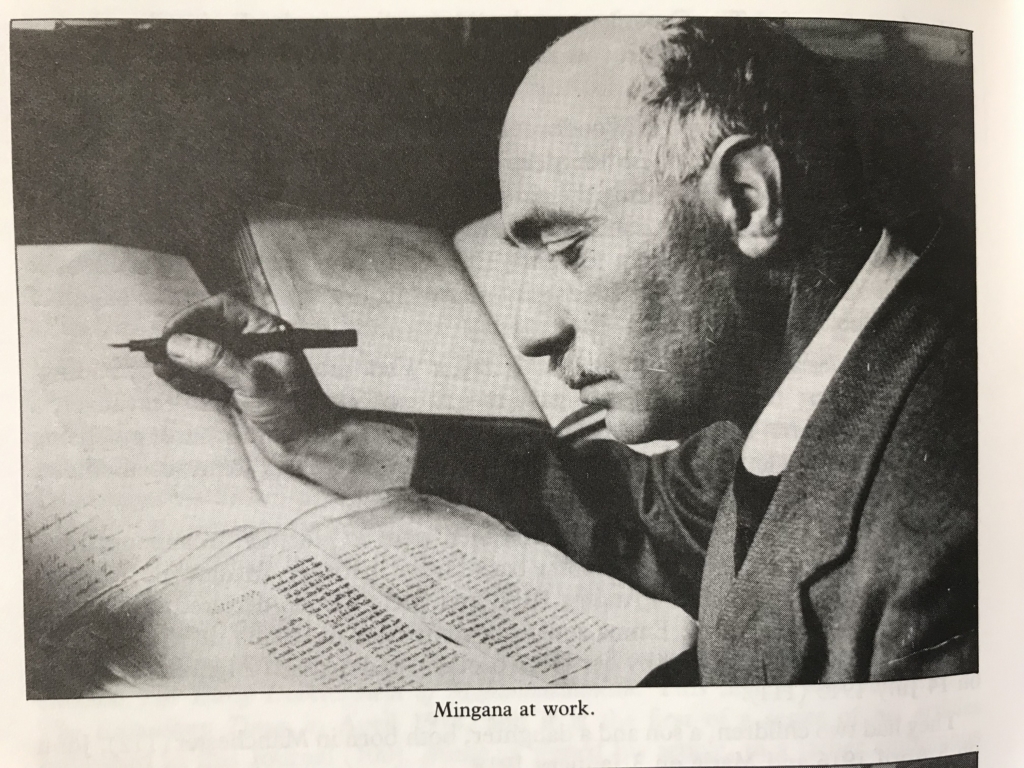

Alphonse Mingana

Did you know that the University of Birmingham in England has a manuscript collection of approximately 3,000 Middle Eastern manuscripts, all of which were collected by an Assyrian named Alphonse Mingana? Over half of the collection, which is known as the “Mingana Collection,” contains Arabic manuscripts. However, the collection also has approximately 660 Syriac and Garshuni (Arabic texts written with Syriac letters) manuscripts. Additionally, there are some manuscripts in several other languages as well, including Armenian, Coptic, Hebrew, and Persian. Some of the Mingana Collection has been digitized and can be viewed online here.

Alphonse Mingana was born Hurmiz Mingana in 1878, in the village of Sharanish in Northern Iraq. His family was Chaldean Catholic, so they sent Mingana to the Séminaire Saint Jean, a Dominican seminary in Mosul, Iraq, when he was approximately 13-years-old. While there, he studied under Eugene Manna, a Chaldean priest and linguist who wrote an Assyrian-Arabic dictionary in 1900. In 1902, Manna became a bishop while Mingana received his ordination as a priest and took on the name “Alphonse.” Because Manna received new responsibilities as a bishop, Mingana replaced him as the Syriac teacher of the Dominican seminary.

While working at the Séminaire Saint Jean, Mingana oversaw the publication of religious books while also attempting to collect Syriac manuscripts. Unfortunately, these manuscripts were destroyed during World War I. Mingana also wrote a Syriac grammar during this time. In 1910, Mingana had a theological quarrel with his church, so left the seminary as well as the priesthood. He then traveled to the Ottoman Empire where he met an American Protestant missionary in Mardin [Turkey]. Through this missionary, Mingana connected with Woodbrooke, a Quaker study center in Birmingham, England.

In 1913, Mingana traveled to Woodbrooke where he eventually began teaching Semitic languages. Its founder, Edward Cadbury, was a Quaker businessman and philanthropist who worked for his family’s chocolate company, Cadbury Brothers. Cadbury ultimately sponsored Mingana to take three trips to the Middle East to collect Middle Eastern manuscripts and bring them back to Woodbrooke. That is how the University of Birmingham’s Mingana Collection was born, since the University now owns Woodbrooke’s Collection. Not only did Mingana collect thousands of important Middle Eastern manuscripts, including one of the oldest fragments of the Quran ever discovered, but he also worked on cataloging them and translating the most important ones into English.

Mingana passed away in Birmingham, England in 1937. He left behind a Norwegian wife and two children.

Written by Esther Lang

Bibliography

“Alphonse Mingana: Famed Orientalist, Discoverer of Important Old Documents of World Value Dies in England at 55.” The New York Times. December 6, 1937. https://www.nytimes.com/1937/12/06/archives/alphonse-mingana-famed-orientalist-discoverer-of-important-old.html (accessed August 30, 2021).

“Alphonse Mingana, Papers of.” Archives Hub. https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/c514d286-9a58-307b-94f4-db203513701c (accessed August 30, 2021).

Bilefsy, Dan. “A Find in Britain: Quran Fragments Perhaps as Old as Islam.” The New York Times. July 22, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/23/world/europe/quran-fragments-university-birmingham.html?searchResultPosition=4 (accessed August 30, 2021).

Emma Sophie Floor Mingana. Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/107136737/emma-sophie-mingana (accessed August 30, 2021).

“History of the Mingana Collection.” University of Birmingham. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/facilities/cadbury/birmingham-quran-mingana-collection/mingana-collection/history.aspx (accessed August 30, 2021).

“Introduction.” University of Birmingham. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/facilities/cadbury/birmingham-quran-mingana-collection/mingana-collection/introduction.aspx (accessed August 30, 2021).

Kiraz, George. A. “Mingana Alphonse.” In Mingana, Alphonse. Edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron M. Butts, George A. Kiraz and Lucas Van Rompay. Digital edition prepared by David Michelson, Ute Possekel, and Daniel L. Schwartz. Gorgias Press, 2011; online ed. Beth Mardutho, 2018. https://gedsh.bethmardutho.org/Mingana-Alphonse (accessed August 30, 2021).

Manna, J. E. Manna. Chaldean-Arabic Dictionary. Beirut: Babel Center Publications, 1975. Edited by Raphael J. Bidawid. https://archive.org/details/chaldean-arabic-dictionar-r.-bidawid-1975/mode/2up (accessed August 30, 2021).

Price, Clair. “Lost Quatrain of Omar Found: Orientalist Discovers Unrecorded Stanza by the Persian Poet in Old Arabic Manuscript in English Museum.” The New York Times. March 14, 1926. https://www.nytimes.com/1926/03/14/archives/lost-quatrain-of-omar-found-orientalist-discovers-unrecorded-stanza.html?searchResultPosition=3 (accessed August 30, 2021).

Samir, Samir Khalil. “Alphonse Mingana: 1878-1937.” Birmingham, United Kingdom: Selly Oak Colleges, 1990. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/alphonsemingana10000sami/mode/2up (accessed August 30, 2021).

Shoumanov, Vasili. “Alphonse Mingana A Prominent Orientalist.” Hagyana Atouraya. May 28, 2021. https://hagyana-atouraya.com/17064/ (accessed August 30, 2021).

Woodbrooke Studies: Christian Documents in Syriac, Arabic, and Garshuni. Vol. 1. Edited by Alphonse Mingana. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons, 1927.