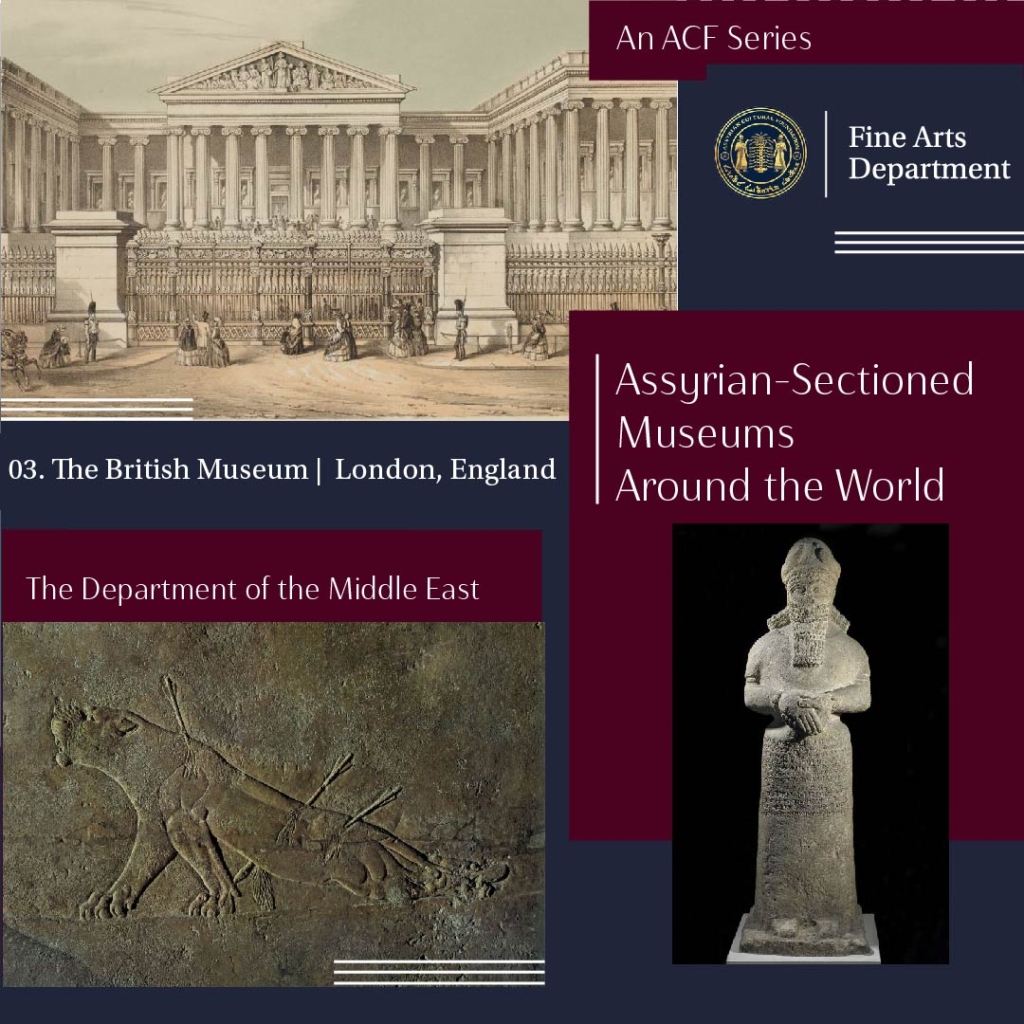

The British Museum: London, England

In our blog on The Metropolitan Museum of Art, we discussed the excavations conducted by Assyrian British diplomat Austin Henry Layard, and Hormuzd Rassam between the years of 1845 and 1851. While a number of their finds did end up in other collections, the majority were sent over to The British Museum. Upon the initial successes of the excavation, The British Museum elected to sponsor Layard and his team. This was done with the expectation that the excavation would serve as a way for the museum to garner new and valuable acquisitions for their collection.

In addition to his discovery of the 9th century BCE Northwest Temple of Ashurbanipal II at Nimrud, Layard also made a number of discoveries at Nineveh. The Assyrian King Sennacherib was known for his building projects. Upon the death of his father Sargon II, Sennacherib left the city of Dur-Sharrukin, and in 701 BCE he established the Assyrian capital at Nineveh where he constructed The Southwest Palace. The palace held over two miles of bas relief sculpture panels. The sculptures recount Sennacherib’s construction endeavors, and provide valuable insight into ancient methods in quarrying and the transportation of such building materials. There are also depictions of the King’s various military campaigns.

In 1851, Layard left for London to pursue a political career. Hormuzd Rassam continued the excavations at Nineveh. During this time, Rassam developed a rivalry with French archaeologist Victor Price. Rassam disregarded established agreements on where the British were allowed to excavate, and snuck onto the French portion of the excavation site in the middle of the night, where he and his team uncovered the North Palace of Ashurbanipal in December of 1853.

King Ashurbanipal’s reign lasted from 669 to 627 BCE, and he is one of the most noteworthy Kings from Assyrian history. Ashurbanipal’s reign was characterized by both conflict and expansion. Upon the death of his father Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal was appointed the King of Assyria, while his older brother Shamash-shum-ukin was appointed King of Babylonia. Though Esarhaddon intended to designate the Kings as “equal brothers”, this appointment began to sow seeds of animosity between them, which eventually led to a civil war which lasted from 652 to 648 BCE. Ashurbanipal was exceptionally adept in his militaristic knowledge and prowess, and the war ended with the seizure and eventual fall of Babylon. At the end of the conflict, the city of Babylon was set ablaze, and according to folklore, Shamash-shum-ukin met his end by means of walking into the flames of his failed empire. The reality of Shamash-shum-ukin’s death remains unknown, as texts only specify that the gods had “consigned him to a fire and destroyed his life.”

It was after the end of the civil war that Ashurbanipal was able to turn his focus to cultural pursuits. He began construction of the North Palace at Nineveh in 646 BCE. Like other Assyrian palaces, the walls were lined with stone bas relief sculptures which feature depictions of the king conducting military campaigns and hunting lions. However, the reliefs at the North Palace also deviate from established traditions. There is a greater variety in the depictions of subjects. Ashurbanipal is shown adorned in various outfits depending on the occasion, and depictions of Non-Assyrian subjects, such as Elamites, Urartian’s, Egyptians, and Arabs, are not only differentiated by means of clothing and equipment, but also by means of different physical features.

In addition to the reliefs, the North Palace also held the Library of Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal prided himself on his extensive scholarly knowledge, and regarded the acquisition of literature as a divine obligation. It was the most extensive library in the ancient world, and contained many of the world’s oldest stories such as The Epic of Gilgamesh and Emuna Elish. Ashurbanipal is presumed to have died in 631 BCE. Just two decades after his death the Assyrian empire collapsed, and the Library of Ashurbanipal was set ablaze during a Babylonian seizure of the city, just as Babylon had burned years prior. While the fire destroyed much of the library’s contents, one exception was the clay cuneiform tablets and cylinder seals. The high temperatures cured the clay, and helped the objects to remain preserved up until their modern discovery.

The Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities was started in 1825 with donations from Claudius James Rich’s collection of Mesopotamian objects. However, the vast majority of the collections most valuable items were obtained during the excavations of Austin Henry Layard, and Hormuzd Rassam. The relief panels, as well as the contents of the Library of Ashurbanipal were sent to the British Musuem via raft down the Tigris River, and have remained there ever since. The department was renamed twice, first to the Department of Ancient Near East, and then to The Department of the Middle East, which it is known as today. The department houses nearly 330,000 works, making it the largest collection Mesopotamian antiquities outside of Iraq. The art discovered at Nimrud and Nineveh illuminated our understanding of just how advanced and powerful the Assyrian empire was, and The British Musuem is incredibly lucky to be in possession of such valued treasures from the Assyrian community’s history.

Bibliograghy:

Amin, Osama S. M. “Wall Reliefs: Ashurnasirpal II at the North-West Palace – World History et Cetera.” Worldhistory.org, https://etc.worldhistory.org/exhibitions/wall-reliefs-ashurnasirpal-ii-north-west-palace/

“Assyrian Sculpture and Balawat Gates.” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/galleries/assyrian-sculpture-and-balawat-gates.

“Assyria: Nineveh.” The British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/collection/galleries/assyria-nineveh.

“Assyria: Nimrud.” The British Museum https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/galleries/assyria-nimrud

Brereton, Gareth. “Introducing the Assyrians.” The British Museum, 19 June 2018, w ww.britishmuseum.org/blog/introducing-assyrians.

“British Museum Department of the Middle East.” Wikipedia, 10 Apr. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Museum_Department_of_the_Middle_East Accessed 9 Feb. 2023.

The Department of Near Eastern Studies. “Early Excavations in Assyria.” Metmuseum.org, Oct. 2020, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rdas/hd_rdas.htm.

Richard David Barnett, and British Museum. Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668-627 B.C.). London, British Museum Publications For The Trustees Of The British Museum, 1976.

Zaia, S 2019, ‘ My Brother’s Keeper: Assurbanipal versus Samas-suma-ukin ‘, Journal of ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 19-52. https://doi.org/10.1515/janeh-2018-2001