The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures

The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures

Chicago, Illinois. United States

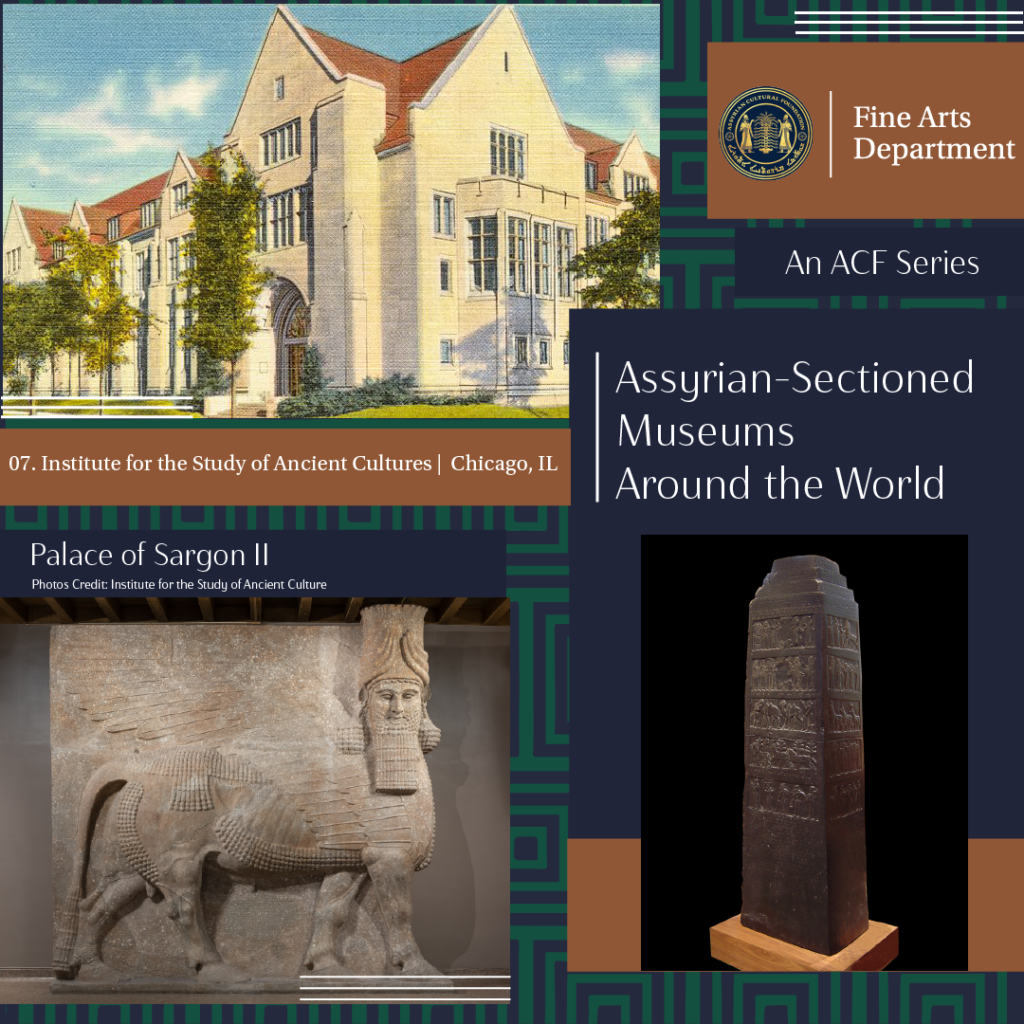

The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, formally known as The Oriental Institute, is a part of the University of Chicago’s department of Near Eastern Studies. The University itself has a long history with Ancient Near Eastern Studies since its founding in 1891. The first president of the University of Chicago was William Rainey Harper, a professor of semitic languages. In addition, his brother, Robert Francis, was also an Assyriologist. The pair both taught classes in their respective fields at the university. They moved the department of Near Eastern Studies into the Haskell Oriental Museum in 1896. The collection was initially quite small, until the Oriental Institute began to fund their own excavations in 1903. Alongside these excavations being conducted in Iraq, The Oriental Institute also began sending researchers and photographers to study ancient inscriptions in Nubia and Egypt.

James Henry Breasted, an Egyptologist, was active in the research being conducted in Nubia and Egypt. He had great aspirations for the sharing of the ancient knowledge of the Near East, and hoped to build an institution that allowed him to share that knowledge with the public. This enthusiasm caught the attention of JD Rockefeller, who also contributed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection of Assyrian artworks. In 1919 Rockefeller made large donations to the Oriental Institute research laboratory, during which time the museum as an entity was formally established. In 1931, Rockefeller’s financial support provided the museum the opportunity to relocate to what is now their permanent location.

One quality that makes The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures unique is that a vast majority of their collection was garnered during expeditions funded and conducted by the institution. These excavations began before the museum had formally been established and continue up to the modern day in locations such as Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Israel, and Turkey. The first excavation conducted in the near east was organized by Harper in 1903. Known as the “Oriental Exploration Fund (Babylonian Division) of The University of Chicago”, Harper and his team traveled out to Bismya, Iraq, and began their dig on Christmas Day of that same year. The excavation uncovered the ancient city of Adab, which was occupied from 3400 BCE to 1150 BCE. Within the remains of the city the team discovered temples, palaces, a ziggurat, tablets, and a cemetery.

In the Spring of 1920, Breasted visited Khorsabad for the first time. He knew of the treasures of King Sargon II’s palace that had been discovered by the French decades before, and believed there was still a great deal beneath the surface waiting to be unearthed. In the years following Breasted’s visit, the University of Chicago also sent Edward Chiera, a newly employed professor at the university, to visit the site as well. During his visit, locals revealed to him a fragment of an Assyrian relief featuring two horseheads that was discovered emerging from the ground, confirming that there were still artifacts to be discovered at the site. The Oriental Institute then received permission to conduct excavations at Khorsabad between the years 1928 to 1935. In April 1929 the museum made one of its most significant discoveries, a full lamassu statue outside the throne room of Sargon II. The statue was hidden under a pile of debris from another building, which partially protected the statue from accruing further damage over time. Upon the discovery, Chiera sent a cable to Breasted describing the discovery and inquiring: “cost transportation about ten thousand dollars (stop) … shall we ask for bull (stop)”. Despite not having the money or resources in the budget to transport such an item, Breasted insisted it was a necessary addition to their collection. The Department of Antiquities of Iraq generously gifted the lamassu to the Oriental Institute, and Pierre Delougaz was put in charge of the challenging transportation back to the museum. The lamassu was reassembled and restored on site at the museum where it was built into the walls of the gallery and remains to this day.

Of all of the museums we have talked about in our series, The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures is the most easily accessible to Chicago residents. The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures continues to be a leader in research conducted in the Near East and works to expand both their own and the public’s understanding of the great societies that once inhabited the area. Given the high population of Assyrians in the city of Chicago, it is incredibly meaningful for such an institution to exist and provides a convenient opportunity for Assyrians to experience pieces of their history in person.

Written by: Melanie Perkins

Bibliography

Loud, Gordon. Khorsabad, Pt. 1: Excavations in the Palace and at a City Gate. 1936. Oriental Institute Publications v. 38.

“Highlights from the Collections | the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.” Oi.uchicago.edu, oi.uchicago.edu/collections/highlights-collections. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

“History of the Oriental Institute | the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.” Oi.uchicago.edu, oi.uchicago.edu/about/history-oriental-institute. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

“In the Beginning | the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.” Oi.uchicago.edu, oi.uchicago.edu/research/beginning. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

“The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.” Oi.uchicago.edu, oi.uchicago.edu/.

“The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.” Oi.uchicago.edu, oi.uchicago.edu/. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023