The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

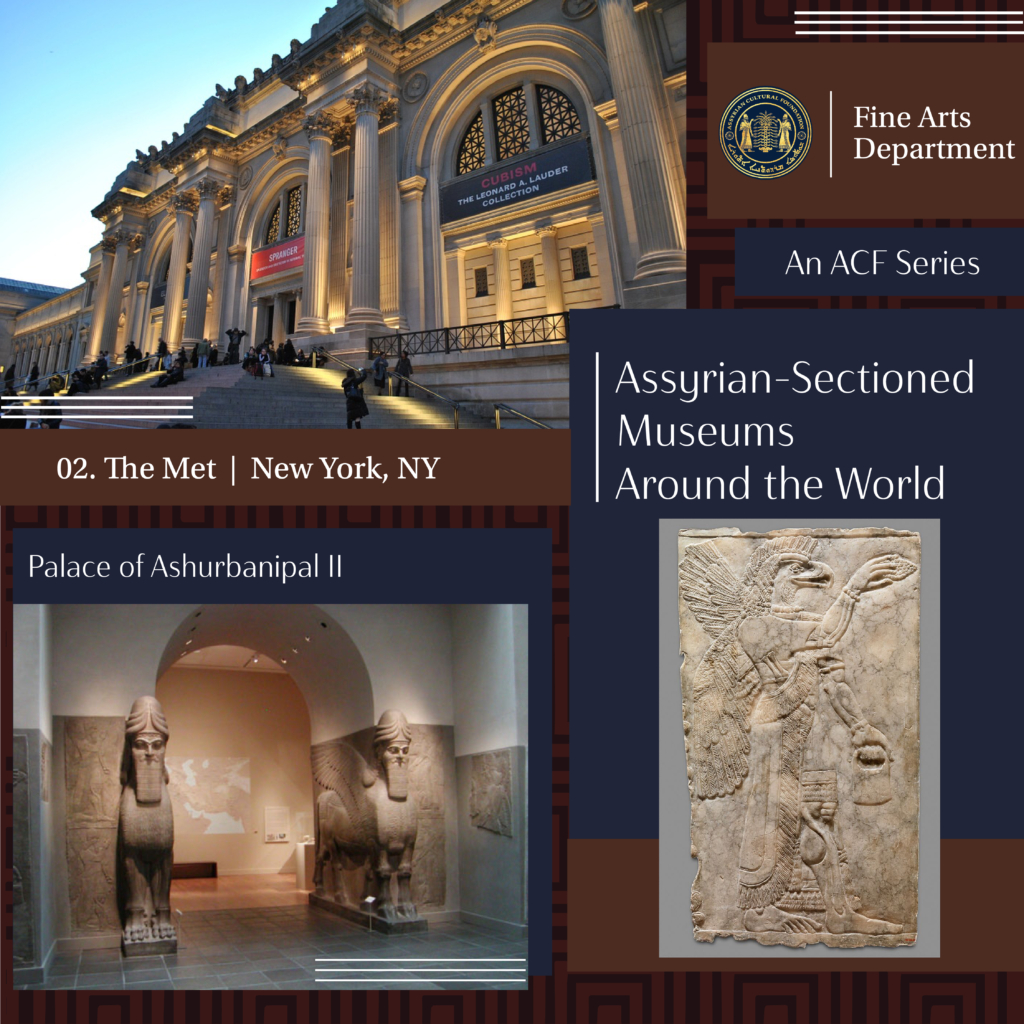

New York City, New York. United States

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City established The Department of Near Eastern Art in 1956. Many of the objects in the collection were excavated in the 1840’s by Englishman Austin Henry Layard. Layard began his excavations at Nimrud (known as Kalhu by Assyrians) in 1845. Nimrud was a prominent Assyrian city since 1350 BC and was established as the capital of Assyria in 864 BC by the King Ashurbanipal II, who moved his capital to a newly created palace that became the largest in the ancient world. Nimrud remained the capital until 701 BC, when Sargon II moved it to Dur- Sharrukin. As a result of the city’s long standing importance in the empire, several royal palaces were constructed over the centuries, and as a result Layard discovered a linty of antiquities at the site.

The reliefs from Nimrud are unique in their portrayal of physical strength, masculinity, and majestic dignity of the human and divine figures. One has the impression that the same artist must have created them. Unfortunately, we do not know who it was.

Layard worked alongside his Assyrian assistant Hormuzd Rassam, and together with their team they also uncovered the Northwest Palace of Ashurbanipal II (reigned 883-859 BCE). It was a mudbrick palace, the walls of which were decorated with bas-relief stone slabs. The slabs are carved out of gypsum alabaster, and microscopic remnants of pigment serve as evidence that the reliefs were once brightly painted. They feature depictions and inscriptions of the King’s accomplishments during his rule. This inscription, known as the Standard Inscription, is unique to the reliefs at the Northwest Palace. It describes Ashurbanipal’s success in construction projects, such as being the first Assyrian King to discover and utilize gypsum alabaster to line the mud brick walls of the palace. The Standard Inscription also catalogues the King’s successful military campaigns. After Layard retired his career as an archeologist, Rassam took over the excavation on behalf of the British Museum in London. Rassam would later conduct excavations at Nineveh as well.

The majority of the works discovered by Britian and France during the 1840’s excavations were sent to The British Museum, and the Louvre. However, many were also acquired by American missionaries and private collectors. Layard himself sent a sent a number of reliefs, including a set of lamassu, to his cousin Lady Charlotte Guest at Canford Manor. Among the private collectors who came into possession of these antiquities, one may recognize some noteworthy figures.

The collection ancient near eastern art at The Met began in 1884 with a donation from Benjamin Brewster, one of the original trustees of Standard Oil. In 1917, JP Morgan donated a selection of Assyrian works as well. The works that Layard had sent to Lady Charlotte Guest changed hands between private collectors in 1919, and in 1932 JD Rockefeller donated eighteen of the sculptures to the museum.

Up until 1932 these Assyrian antiquities were managed by the Department of Decorative Arts. As the collection grew, it became necessary to create a new separate department, The Department of Near Eastern Art. In March of 1949 Max E.L. Mallowan, a British archeologist, reopened excavations at Nimrud, of which the Metropolitan Museum of Art was a major financial contributor. This series of excavations yielded for the museum their collection of Assyrian ivories as well as many other smaller art objects. As the collection continued to rapidly expand, the museum eventually ran out of display space, and was forced to put many of the Assyrian pieces in storage.

In 1956 the department was renamed for a last time to The Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. The miniscule name change can be seen as the first in a series and developments and updates the department would go through in the following years. Some of the most noteworthy changes related to the curation of the space. In 1961, the curator of the department Charles K Wilkinson opened two new galleries in the museums north wing. This allowed Wilkinson to take Assyrian antiquities out of storage, and have a larger volume on display in the museum. He also took the time to arrange the sculptures in the same manner they were originally displayed in the Northwest Palace, to the best of his ability.

Today, The Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art provides visitors the opportunity to embark on a journey through the ancient world. The exhibitions start in the Neolithic period, with humans beginning to settle in the world’s first cities and cataloguing their own history through the development of a written language. From there, the galleries continue chronologically up to the fall of the Assyrian empire. One of the goals of the department is to “explore(s) cross-cultural themes such as medicine and magic, money and weights, the biblical world, and the relationship between art and text in the ancient Near East” (Ancient Near Eastern Art). The Metropolitan Museum of Art is an expansive collection of art, with pieces from all across the globe that encompass millennia of human history. The museum in all its grandeur presents to us the story of humanity, and The Department of Near Eastern Art offers visitors the ability to start that story from the very beginning.

In 2016, ISIS destroyed the Assyrian artifacts at Nimrud, planting explosives in the ruins that led to shattering the incredible ancient creations, symbols of continued Assyrian existence in Iraq, to pieces. This act prompts us to appreciate what had been preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art all the more today.

Written by: Melanie Perkins

Bibliography:

“Ancient Near Eastern Art.” Metmuseum.org, 2022, www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/ancient-near-eastern-art.

Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “Early Excavations in Assyria.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000- http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rdas/hd_rdas.htm (October 2004; updated August 2021)

Seymour, Michael. “The Assyrian Sculpture Court.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000- http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nimr_2/hd_nimr_2.htm (December 2016; updated January 2022)

Vaughn Emerson Crawford, et al. Assyrian Reliefs and Ivories in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 Oct. 2012.