The Iraq Museum

Date: August 22, 2023

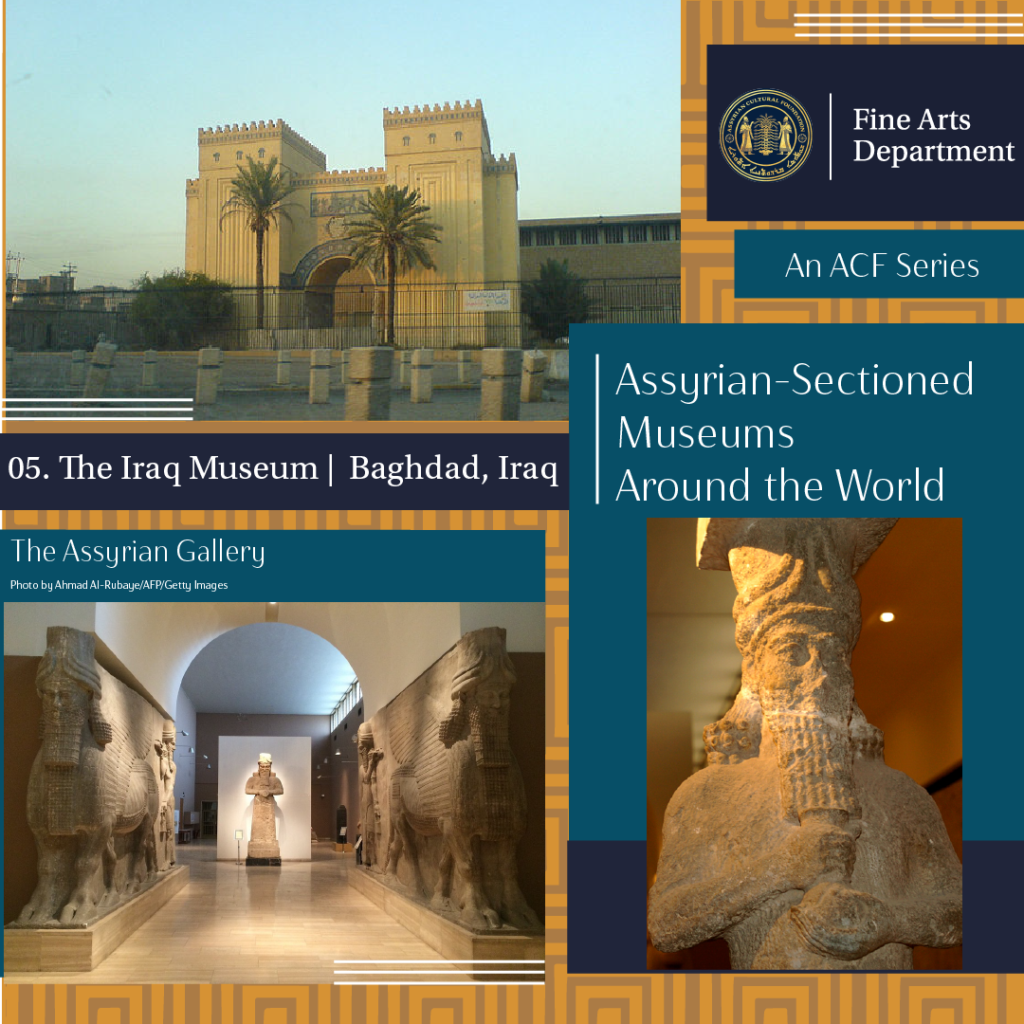

The Iraq Museum

Baghdad, Iraq

As we discussed in our previous museum blogs, after the 19th century exhibitions of Assyrian sites, most of the works were shipped to out of Iraq to museums around the world. However, not all of the discovered Assyrian treasures left their country of origin, as with the collection at The Museum of Iraq in Baghdad.

Compared to the other museums we have discussed so far; The Iraq Museum was established more recently. The Baghdad Archaeological Museum was established in 1926 with the help of British author Gertrude Bell. She sought to prevent archaeologist Leonard Woolley from sending all of his discoveries from the ancient Sumerian city of Ur to Great Britain. She believed that the people of Iraq were owed access to their own history. In 1922, she began storing objects in a government building in Baghdad. The objects were then moved to another building, and the museum was established by the government. In the 1920’s it was under the Ministry of Public Works and was transferred to the Ministry of Education in the 1930s. The buildings of the museum were also constructed utilizing resources from foreign governments. The Old Museum building, Administration Building, Library, and Old Storage Building were built by the German government between 1964 and 1966, and the New Museum Building was built by the Italian government in 1983.

The museum has artifacts from ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian civilizations. One of the most noteworthy collections is the Nimrud gold. This is a set of gold jewelry that was discovered in the royal tombs at Nimrud. The pieces provide insight into the inner workings of Assyrian royal life and funerary practices. The museum also owned a stone statue of Neo-Assyrian King Shalmaneser, son of Ashurbanipal II, from the eighth century BCE. These objects were discovered during a series of excavations at Kalhu (Nimrud) in the 1950’s. The end of WWI and the subsequent fall of the Ottoman Empire made for dramatic political changes in the area which afforded the British new opportunities to conduct excavations again, similar to those conducted in the 19th century by Henry Layard and Hormuzed Rassam. This 20th century excavation was to be led by Max Mallowan, husband of famed mystery author Agatha Christie. Mallowan was aware of the impact of Christie’s celebrity on the reception of the excavation. He even arranged “tea with Agatha” meet and greets with financial supporters of the excavation, such as the Iraq Petroleum Company. This excavation differed from those prior in a number of impactful ways.

For the first time in the history of excavations at Assyrian sites, Iraqi authorities and professional archeologists were on site at the dig. Their presence served to ensure that the most significant discoveries stayed within the country at the Iraq Museum. Iraqi conservators also started the process of restoring and preserving the site of Nimrud, with the intention of preparing it for future visits from tourists.

The conservators’ aspirations for the future of these archeological sites unfortunately never came to fruition. The Iraq Museum continued to operate and expand the collection of ancient Mesopotamian objects, until 1991. The Gulf War marked a time period of extreme political unrest in Iraq, and The Iraq Museum was forced to close as a result. The museum was reopened in 2000, during the reign of former president Sudam Hussain. Unfortunately, the reopening of the museum was done as an act of political propaganda, intended to present the appearance of stability and unity within the country. The safety of the museum staff and its contents was not assured by the reopening. During the Iraq War in 2003, museum staff was asked to exit the museum for their safety, as its location had put it in cross fire between American and Iraqi forces. This opened the museum up to looters. The worst of the looting took place between April 7-12th at which point museum staff returned to the institution. The staff fended off further looting attempts on their own until American forces arrived on April 16th to secure the building. Despite the efforts of the staff, the museum faced significant losses, many of which have never been recovered. The Iraq Museum was not the only historical site that suffered at the hands of looting. The result of this is that the current staff at the museum are regularly tasked with the challenge sorting through countless looted objects as they are seized at border crossings. Another challenge face by The Museum of Iraq is the preservation of historical objects, both in the museum and at the sites of their discovery. Historical sites such as Nineveh have been used as dumping grounds for garbage. Videos of terrorists’ groups destroying Assyrian monuments have been filmed and posted as recently as 2015. The destruction of a nation’s history in this manner is a war crime, and to this day the perpetrators have yet to be brought to justice.

The Iraq Museum has faced significant challenges in obtaining, securing, and sharing its collection of ancient Mesopotamian art. However, despite the obstacles, the staff remains committed to protecting and continuing to learn from the diverse history of all of the peoples and civilizations within the region. Due to the persecution they faced in the region, many Iraqi Assyrians are not able to return to their home country. The presence of the Iraq Museum and its collection of Assyrian objects shows just how important and significant Assyrian history is to the region, and demonstrates the necessity in creating a space for all of the citizens of Iraq to engage with, learn from, and share their history with pride.

Written by: Melanie Perkins

Published by: Brian Banyamin

Bibliography:

Fantastic Jewlery from Nimrud – FEEFAA.org. www.feefaa.org/fantastic-jewellery-from-nimrud/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

“Iraq Museum.” Wikipedia, 5 Feb. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iraq_Museum. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

“Learning from the Iraq Museum.” American Journal of Archaeology, 1 Oct. 2010, www.ajaonline.org/online-review-museum/364.

“Remnants of Empire: Views of Kalhu in 1950.” Oracc.museum.upenn.edu, http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/modernnimrud/onthemound/1950/index.html. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

“The Iraq Museum | the Iraq Museum.” Www.theiraqmuseum.com, www.theiraqmuseum.com/.