The Brooklyn Museum

Date: September 18, 2023

The Brooklyn Museum

Brooklyn, New York. United States

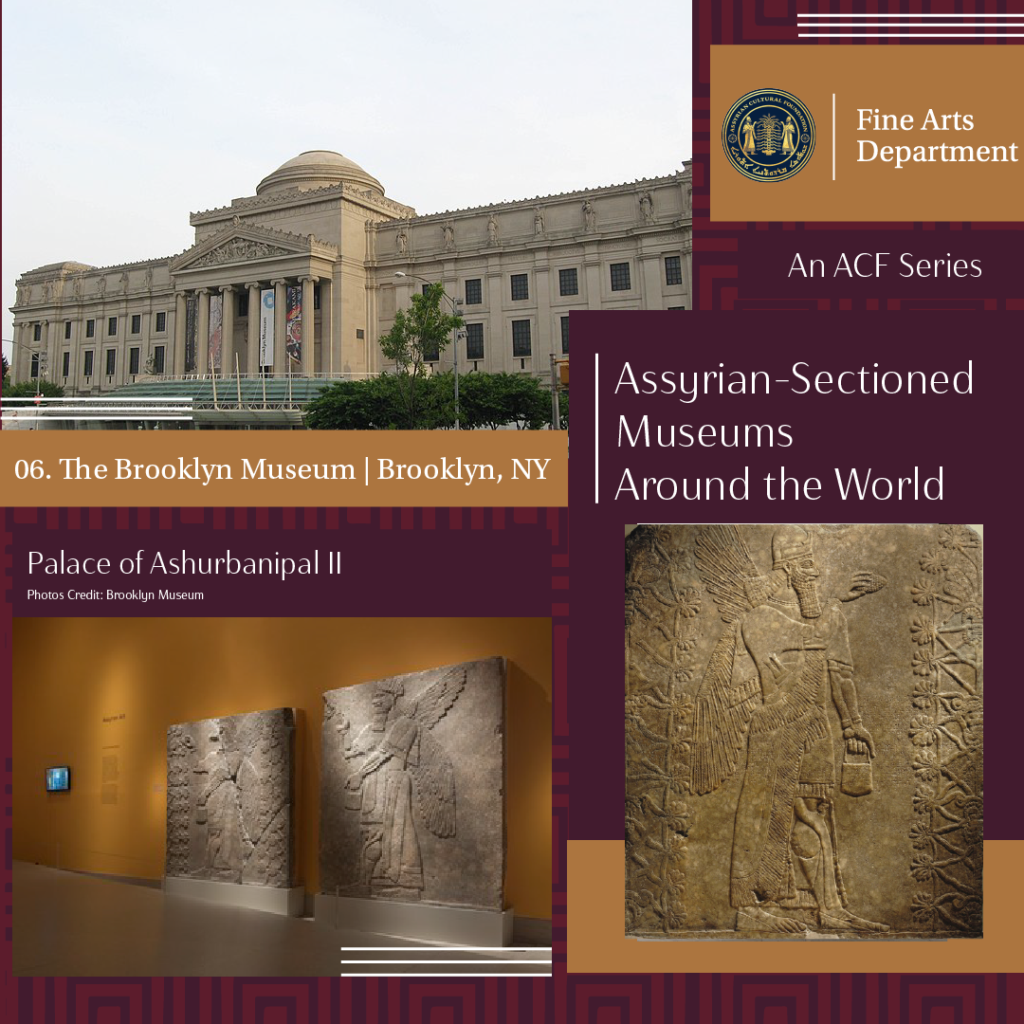

The next museum we are going to cover is one of the more recent acquisitions of Assyrian art to a museum collection. The Brooklyn Museum in Brooklyn, New York, was founded in 1898 as an offshoot of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. The goal of the institution is to be “a powerful place of personal transformation and social change”.

The Brooklyn Museum is in possession of a series of twelve reliefs from Ashur-nasir-pal II’s palace at Kalhu from 879 BCE. Upon completion of the palace, the King hosted a gala during which citizens were able to walk through the palace to admire its beauty. It is believed there were nearly 70,000 guests in attendance at this celebration. These reliefs were unearthed during the 1840’s excavations of British archeologist Austen Henry Layard, which we discussed in earlier articles. As you may recall, the British and French excavation teams developed a rivalry over the course of their discoveries. The escalating competitive attitudes are part of what motivated the teams to rapidly gather and ship as many artifacts as they could back to their respective institutions. While we know that the majority of these artifacts still reside in the museums they were initially sent to, the fervor of the excavation teams resulted in the museums acquiring far more items than they had the space to store them. Left with few other choices, the museums put some of the artifacts up for sale on the private market.

It was in 1855 when Henry Stevens, an American, purchased the reliefs in London. His initial intention was to send the reliefs to Boston where they would become property of the city. However, Boston municipal authorities were not able to raise the necessary funds to purchase the works from Stevens. As a result, Stevens began seeking buyers in New York City. James Lenox, of the New York Historical Society in Manhattan ended up purchasing the works. The reliefs were held by the New York Historical Society in Manhattan until 1937, when they lent the works to the Brooklyn Museum due to constraints in resources and storage space. Though the museum now held and displayed the works, they did not have the funds to purchase them outright. That was until 1955.

Hagop Kevorkian was a collector and dealer of ancient near eastern art in New York. Kevorkian was from the city of Kayseri in Turkey, and graduated from the American Robert College in Istanbul. He came to New York as a young man in the 19th century. He made a name for himself through his contributions of antiquities for a number of noteworthy institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Louvre, The Victoria and Albert Museum, The University of Pennsylvania Museum, and The Brooklyn Museum. Hagop Kevorkian provided the funds to the Brooklyn Museum to purchase the twelve Ashur-nasir-pal II reliefs and install them in the space, which was aptly named the Hagop Kevorkian Gallery of Ancient Middle Eastern Art.

This set of reliefs features depictions of Ashur-nasir-pal II communicating and consorting with divine entities. In addition to serving as a political leader, the Kings of ancient Assyria served as religious leaders as well. They were expected to demonstrate both an understanding and commitment to the Gods and Goddesses of the ancient Assyrian pantheon. Most of the reliefs feature apkallū -figures, also known as Genies. Genies are a divine winged being that served as the Kings protectors and consorts. Apkallū were seen as exceptionally intelligent, and were imagined to have assisted in the construction and protection of cities and their inhabitants. The relief show the King and genies celebrating religious rituals, such as tending to the sacred tree of life. The tree of life symbolism in particular was a motif used in Assyrian art to represent the divine power of the King to bestow life. The tree of life symbolism is so quincuncial to Assyrian art, that it is also used as the inspiration and subject of the logo for The Assyrian Cultural Foundation.

Though many institutions have a larger variety of works from Assyrian, the Brooklyn Museum succeeds in providing guests an in depth look at the royal life of on Assyrian King and thus allows for a more personal and insular contemplation of the art at hand. By having the reliefs isolated from the wide variety of art that appears throughout the timeline of the empire, it allows for the details and nuances them to become more noticeable. Just as guests walked through the palace walls in 879 BCE, now visitors to the Brooklyn Museum can walk alongside these reliefs can contemplate the remarkable accomplishments of this ancient empire.

Written by: Melanie Perkins

Published by: Brian Banyamin

Bibliography

“Brooklyn Museum: About the Museum.” Www.brooklynmuseum.org, www.brooklynmuseum.org/about .

“Brooklyn Museum.” Www.brooklynmuseum.org, www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/70571 .

“Hagop Kevorkian.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 6 Oct. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagop_Kevorkian.

“Selected Works of Ancient near Eastern Art, Including Assyrian Reliefs.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/exhibitions/3206.